On the 12th day of Christmas, generous donors gave to us…

RSS Feed...parts of a Roman equestrian statue and an Iron Age moustache!

The archaeological collections at the museum have been enhanced by more generous donations of important and intriguing objects by members of the public. Following the donation of a fascinating Roman phallic carving at the end of 2015 (see our blog post on it here), we are delighted to announce some equally significant new acquisitions.

Roman copper alloy equestrian statue fragments, from North Carlton

Although at first glance they look rather like pieces which have fallen off a tractor, these copper alloy fragments form part of one of the most fascinating discoveries in Lincolnshire's Roman archaeology in recent years, and are a find of national importance. The significance of Lincoln as a Roman Colonia is well known, and foremost among the suite of public buildings that would have graced the Roman town were the forum and basilica - the administrative and commercial heart of the city. The Roman forum was situated to the west of modern Bailgate, and those familiar with the city may already be aware of the Roman well that still survives, and of the cobbled setts that mark the position of the towering sandstone columns that ran around the edge of the forum complex. It has long been assumed that, as the central point of a major settlement, the forum would have been adorned with decoration and statuary, depicting prominent local citizens and Emperors. Seminal excavations in the forum in 1972 revealed a stone statue base, but up until recent years the only evidence of the statuary itself has been in the form of a bronze horse's foreleg, discovered in the 19th Century and now in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Two recent discoveries have added to our understanding. One was the excavation of a small copper alloy eagle's wing at Lincoln Castle in 2013, found in a late 1st Century AD context, and therefore relating to the earliest years of the Colonia, which was founded at some point between c.AD84 and c.AD96. Discovered along with Roman buildings just inside the eastern walls of the castle, the wing was clearly part of a larger scuplture, but had been deliberately removed. Was this eagle, the symbol of Jupiter and of Roman Imperial and military might, part of a larger Imperial statue?

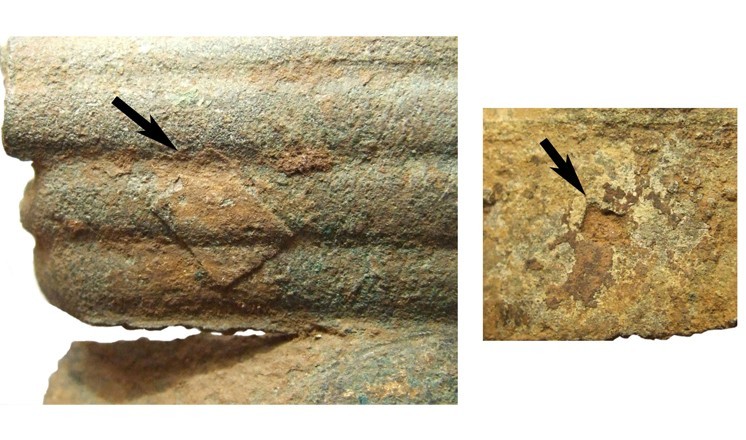

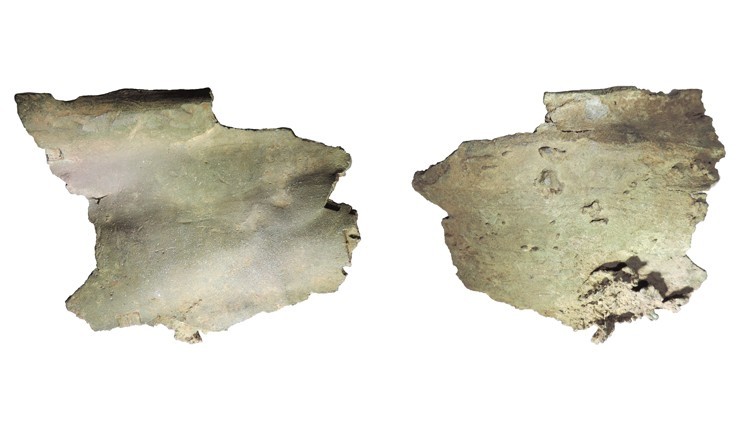

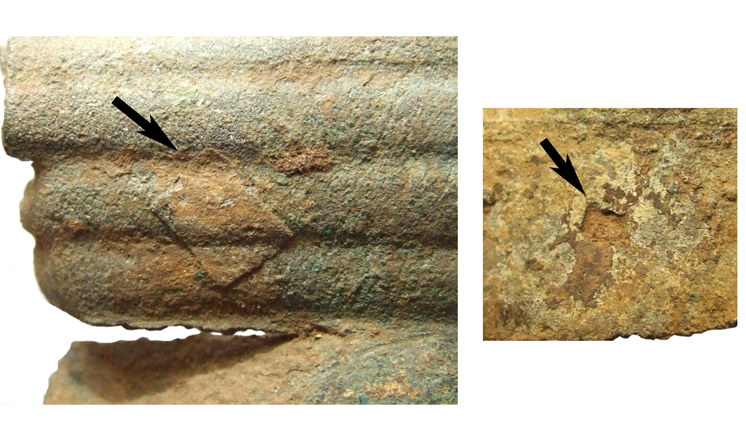

To turn our attention to the newly donated fragments under discussion here, they were discovered at North Carlton (c. 5 miles directly north of Lincoln) in 2010, and have since been undergoing detailed analysis at University College London. A detailed publication on the fragments is forthcoming. The fragments total 8 copper alloy pieces and 2 lead pieces, some of which have been identified as coming from specific parts of the statue, particularly those from the horse's neck, mane, muzzle and bridle. Two of the copper alloy fragments, from the neck and body, have evidence of small rectangular cutaways made in the surface of the statue. These most likely represent either later repairs to damaged areas, or areas where the original bronzesmith was not happy with the quality of the casting. A small section would be removed and replaced with a plug of new copper alloy. A fragment from the horse's mane has also had a small repair, in the form of a small applied patch of copper alloy. You can read more about ancient bronze repair techniques here.

The results of the detailed study of the fragments, carried out by Dr Kosmas Dafas of King's College, London, will be published in due course, and will hopefully add more detail to the story of this important part of Lincolnshire's Roman past.

A consistent factor of all of the statue fragments known from Lincoln is that they have been damaged in some way, and perhaps were all destined for recycling. The 19th Century horse foreleg shows signs of having been involved in a fire, the eagle wing has been deliberately chopped off, and the North Carlton fragments are damaged in a manner consistent with having fallen or been intentionally toppled. That these statues might have been recycled should not surprise us. Bronze was a valuable material in the ancient world, and objects and statues that had become redundant could be melted down and reused in infinite ways. Our lasting image of ancient statuary is of marble sculpture, but the prevelance of ancient bronze recycling has skewed the surviving evidence and tainted our modern perception.

There is, however, another reason why these statues may have been destroyed. The Colonia at Lincoln was established under the reign of the Emperor Domitian (AD81-96). Domitian, a ruthless ruler portrayed as a vicous tyrant by most ancient authors, was subjected to Damnatio Memoriae after his assassination by members of his court - his name stricken from the official records and his images destroyed. It is likely that the fledgling Colonia at Lincoln would have had statues honouring the Emperor that founded it, and these would presumably have been taken down, willingly or unwillingly, by the city's administrators. Does the damage to the known statue fragments reflect, at least in part, the official dismantling of Domitian's image? The eagle's wing is particularly significant in this regard, coming as it does from a secure late 1st Century context and from a site close to the forum complex. Without firm evidence that these statues represent such a specific figure this is of course pure speculation, but it offers a tantalising possibility.

So how might a statue of Domitian looked? Imperial statuary often followed established conventions, and the wonderfully surviving equestrian statue of the later Emperor Marcus Aurelius (AD161-180), from the Capitoline Hill in Rome (you can see it and read about it here) provides a likely comparison. We also have a poem by Statius, who not only lived during Domitian's reign but was one of his most sycophantic supporters. His verse describes an enormous equestrian statue that stood in Rome but is now sadly lost. The full poem can be read here, but his description of the horse is memorable:

A cloak hangs from thy shoulders; the sword sleeps by thy untroubled side: even so vast a blade does threatening Orion wield on winter nights and terrify the stars. But the steed, counterfeiting the proud mien and high mettle of a horse, tosses his head in greater spirit and makes as though to move; the mane stands stiff upon his neck, his shoulders thrill with life, and his flanks spread wide enough for those mighty spurs; in place of a clod of empty earth his brazen hoof tramples the hair of captive Rhine. Seeing him, Adrastus' horse Arion would have been sore afraid, yea Castor's Cyllarus fears as he looks forth upon him from his neighbouring temple. Never will this steed suffer another master's rein; this curb is his for ever, one star, and one star only will he serve. Scarce doth the soil hold, and the ground pants beneath the pressure of so vast a weight; and not of iron or bronze: 'tis under thy deity it trembles, ay, even should an everlasting rock support thee, such as would bear the peaks of a mountain piled upon it, or have endured to be pressed by the knee of heaven- sustaining Atlas.

The statue Statius describes had Domitian holding a figure of the Goddess Minerva in his hand - his favoured protective patron deity - but how would the eagle wing form part of such a statue? The image of an eagle surmounting a globe was an allegory of Roman Imperial domination, and was used by the Flavian dynasty on coinage. It is not too far fetched to suggest that such a symbol might have been held in Domitian's hand instead of the Minerva figurine. Based on this principle, the statue may have appeared roughly as in this recently commissioned reconstruction sketch.

Details of the North Carlton fragments are based on the Portable Antiquities Scheme report produced by Dr Adam Daubney and Dr Kosmas Dafas. The images of the fragments are by Dr Daubney. The Collection is grateful to the finder, Mr Steven Allenby, for his recognition of the significance of the statue fragments and for his generosity in donating them to the museum.

Iron Age 'moustache', from North Rauceby

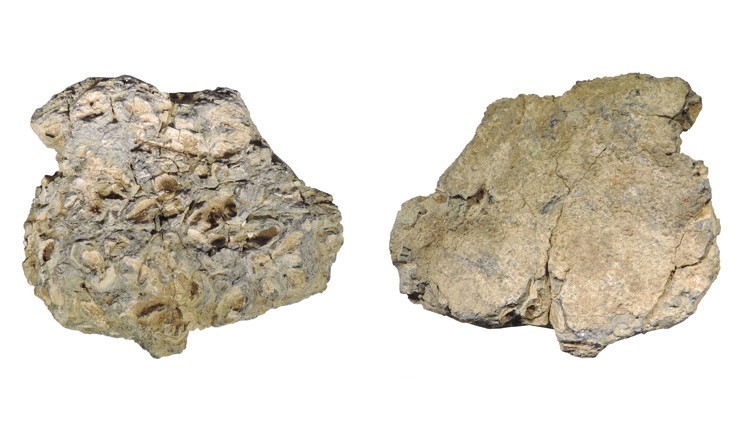

This characterful and unusual object is one of a number now known from Britain, but for which the original function remains a mystery. These fittings - for they were clearly once part of a larger composite object - are in the form of stylised and exaggerated moustaches. This particular example is the first to be added to the museum's collections. It has a central groove with tapering terminals on each side, the central parts of which are ribbed as if to simulate hair. The underside is plain and has a small circular depression. The groove and depression would appear to be the means by which the fitting was attached. Suggestions of how they were used have included dagger terminals and chariot fittings, but only a find of one still in its wider context will confirm the function with certainty.

The dating of these curious objects is also debatable as none have yet been found in a secure archaeological context. The presence of one, stylistically very similar to this example, in the Salisbury Hoard (now in the British Museum) provides some context, but not much. The Salisbury Hoard contains objects from an enormous time span - from the middle Bronze Age (c.1500 BC) to the Iron Age, and the moustache could theoretically come from anywhere in between. General consensus agrees that they are more likely to be Iron Age than Bronze Age, and the prominence of the moustache in Iron Age culture lends weight to this idea. Julius Caesar, writing about the Britons in his Bello Gallico, comments that 'they wear their hair long, and have every part of their body shaved except their head and upper lip'. Moustaches therefore clearly had a specific cultural significance to the Iron Age Britons.

The Collection is extremely grateful to Mr Clive Rasdall for his generous donation of the moustache fitting.

Comments

There aren’t any comments for this blog yet