Of considerable distinction and elegance

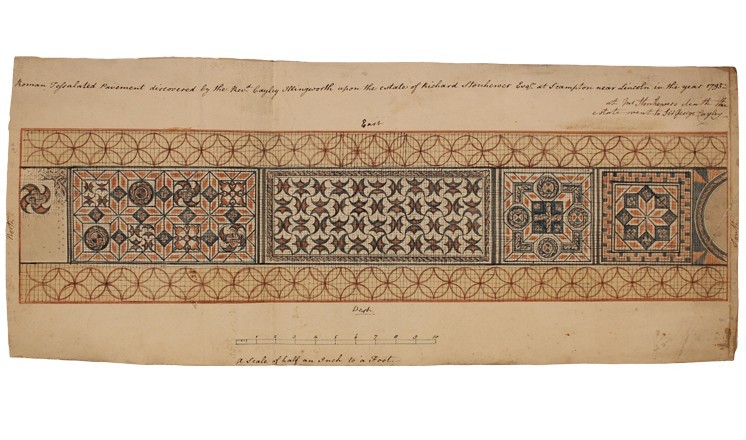

RSS FeedThe Roman villa at Scampton is one of the most important archaeological sites in Lincolnshire. This article provides a contextual overview of the 1795 excavations at the villa, and a discussion of a previously unknown original antiquarian illustration of its most complete tessellated pavement, recently acquired by The Collection museum, Lincoln. The illustration is unsigned and undated and both the identity of its creator and its date of production are proposed.

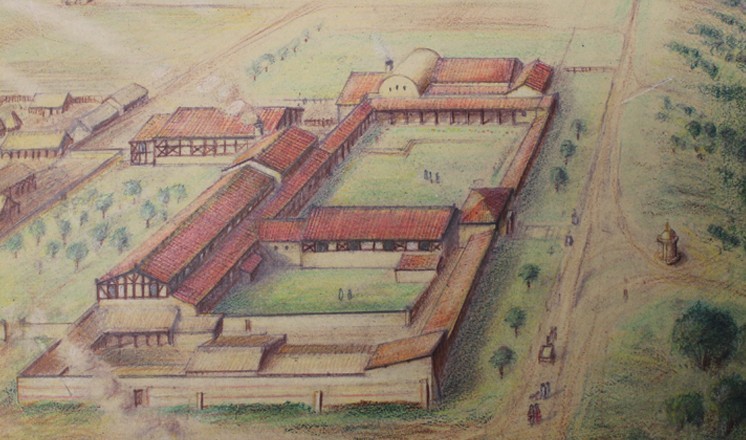

The Roman villa at Scampton, just north of Lincoln, is one of the grandest villas yet known in the county. Situated in a dramatic position on Lincoln edge, 5 miles north of Lindum Colonia, the original occupants would have enjoyed commanding views along the line of the modern Tillbridge Lane, the Roman road leading westwards away from Ermine Street towards the Trent valley. The villa was discovered and excavated in 1795 by the Reverend Cayley Illingworth. In his book on Scampton, originally printed in 1808, he describes the discovery:

"some workmen, digging for stone in a field south-east of the village, and north of Tilbridge-lane, were observed to turn up several red tiles, which, on inspection, Mr Illingworth conceived to be Roman. This induced him to survey the general appearance of the surrounding spot; and being struck with obvious traces of foundations, he directed the men to dig towards them, when they came to a wall two feet beneath the surface, and shortly after to a Roman pavement. The result was, that the foundations of nearly a whole Roman villa were traced and accurately examined; and the situation of the place, the nature of the walls, the dimensions of some apartments, the number and beauty of the tessellated pavements, and the regular plan of the whole, leave little doubt of its having been a villa of considerable distinction and elegance" [1]

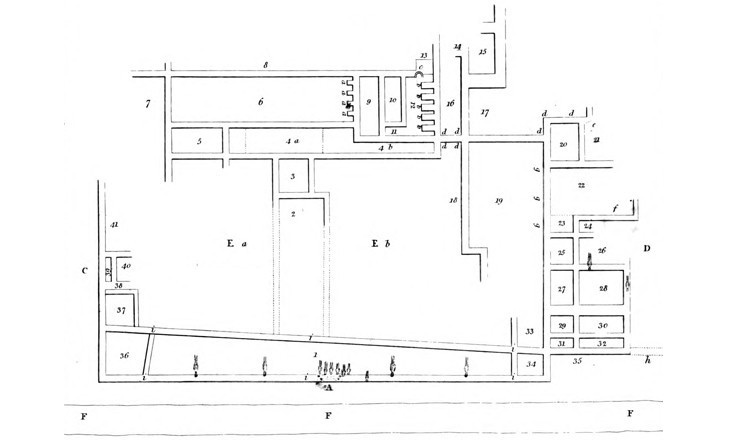

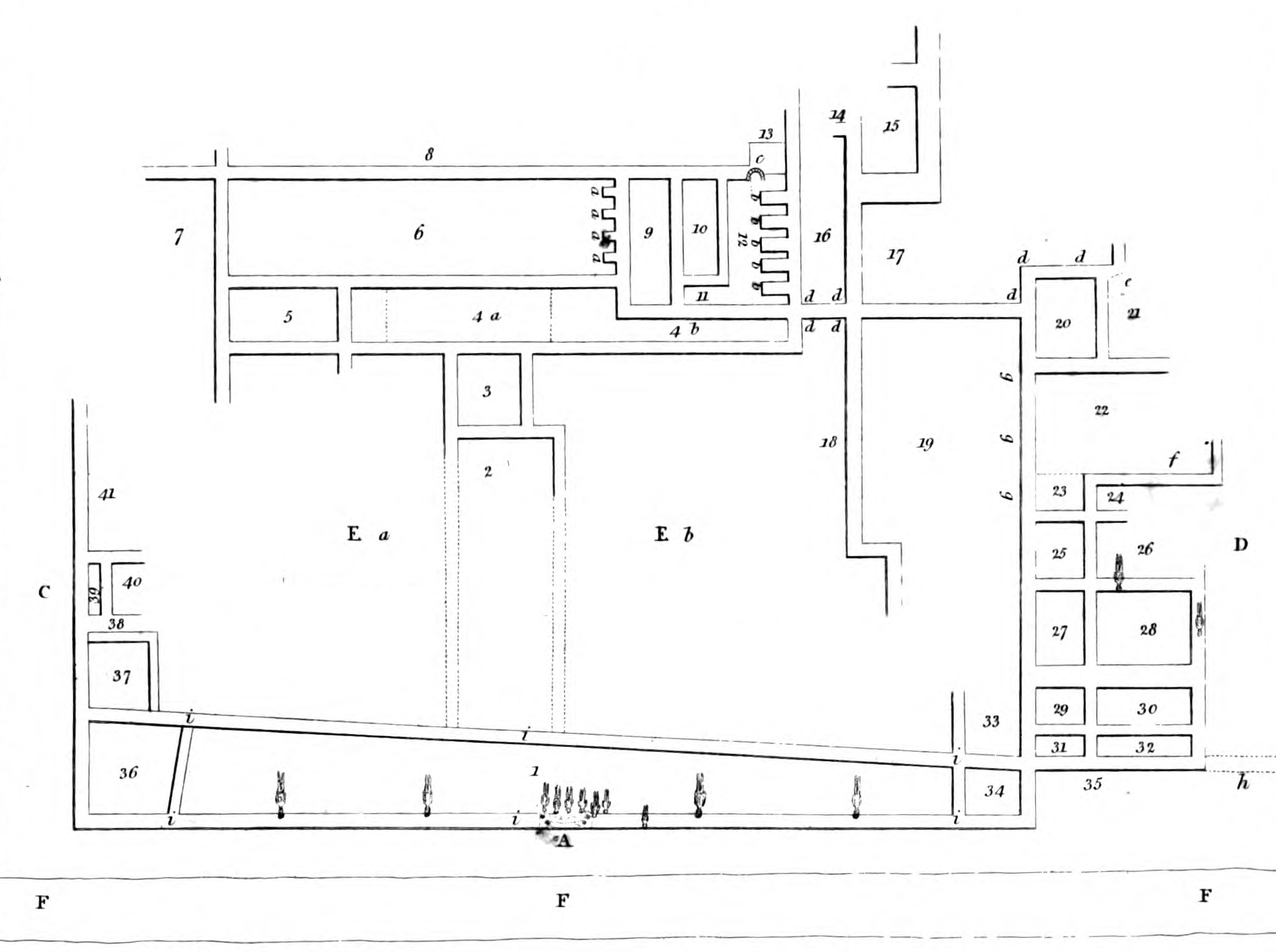

Cayley Illingworth's excavation plan (fig 1) reveals the extent of the villa, with 41 rooms excavated around a double courtyard, with some suggestion that the site continued further, as indicated by unfinished walls on the plan, particularly to the east. The excavations equally did not explore the possibility of other outbuildings surrounding the main villa complex. The double courtyard plan is of interest, as most villas in the area of the Civitas Corieltavorum were of aisled barn or corridor form. The scale, level of decoration and layout all suggest that the original owner of villa wished his house to stand out, and we can perhaps further suggest that this indicates an individual of differing cultural or ethnic background, likely with business interests in the nearby Colonia.

Fig 1: Cayley Illingworth's plan of the villa, 1808

In terms of the villa layout, Cayley Illingworth proposed that the grand entrance to the complex was located at point A on fig 1, meaning that visitors entered from the west, with their backs to the grand Trent valley vista. A monumental oblong stone block of 6' 10" in length, 3' 4" in width (2.08m x 1.02m) was discovered at this entrance, cut with square holes to take gateposts[2]. Visitors would have entered into some form of passageway between the two courtyards, presumably suitably appointed to allow the splendour, and perhaps even the unusual nature, of the villa's layout to be appreciated. This must remain mere speculation, however, as the dotted lines demarking the northern and southern boundaries of room 2 on fig 1 did not produce evidence of solid foundations. Cayley Illingworth suggested that the courtyards may have been kept distinct, with the northern courtyard of lower status and the southern courtyard, surrounded by higher status rooms, of greater importance. The nature of the courtyards themselves is unfortunately unknown, though it is interesting to speculate that they may have contained formal gardens or at least some element of architectural or sculptural adornment.

The western entrance range is also noteworthy for the discovery of 'upward of 20 human skeletons, nearly perfect' [3], buried in an east-west orientation with some interred in coffins. Cayley Illingworth supposed, as we still do today, that the burials represent Early Medieval or Medieval re-use of the site in the post Roman period, perhaps associated with the Medieval Chapel of St Pancras later constructed on the site.

The southern range of rooms (marked D on fig 1) appear to have contained a bath suite, with Cayley Illingworth identifying room 22 as a bath due to clay deposits on the wall foundations and a low floor level [4]. It is therefore likely that surrounding rooms also served a bathing function, though no specific evidence for their function, layout, or substantial evidence for hypocausts is recorded as being discovered. It is possible that the bath suite continued to the southeast, outside of the excavated area.

The opulence of the villa was most dramatically demonstrated through its tessellated pavements. Cayley Illingworth noted that approximately 13 were discovered, though only one in a near complete state. The designs were exclusively geometric, and made from local limestone with tesserae ranging from 'half an inch to an inch and a half square' [5].

The near complete pavement, the only one to be recorded, was discovered in the room marked 4a in Fig 1. This position, in the eastern range facing the main entrance, suggests that it served a very public function as reception room, or at least as a transitory space between various spaces designed for business or conducting client-related activity.

It is to this tessellated pavement, and more specifically to the contemporary illustrations made of it, to which we now turn. The discovery clearly caused a stir at the time, but sadly to the detriment of the remains. Cayley Illingworth tells us:

"When first discovered, the colours of this pavement were extremely bright; which, added to the curiously artificial workmanship, afforded a pleasing specimen of the Roman art. But it shortly after lost much of its original elegance, by reason of several of the tesserae having been picked up by the country people, who flocked in numbers to view it. In order, however, to prevent the pavement sustaining any further injury, a building was erected over it. Notwithstanding this precaution, it is still to be lamented, that the decay of its beauty becomes visibly rapid, from the effects produced by the hands of idle curiosity." [6]

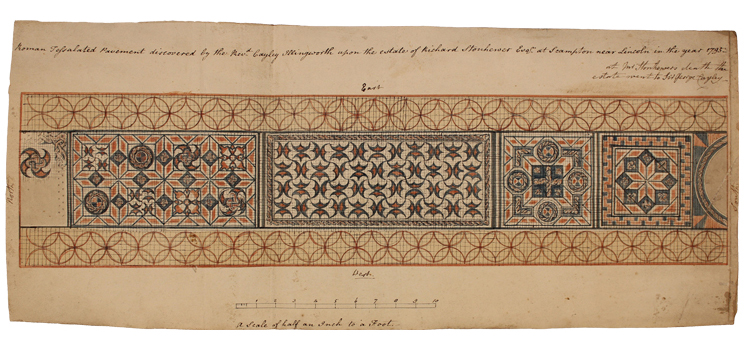

The engraving of the pavement published in Cayley Illingworth's 1808 book (fig 2) was produced by William Fowler of Winterton, an architect and builder who turned his considerable artistic talents into recording archaeological discoveries of the late 18th and early 19th Centuries, and made a national name for himself in the process. His illustrations of tessellated pavements at other great Lincolnshire villas such as Winterton and Horkstow are an invaluable record of now lost or reburied pavements.

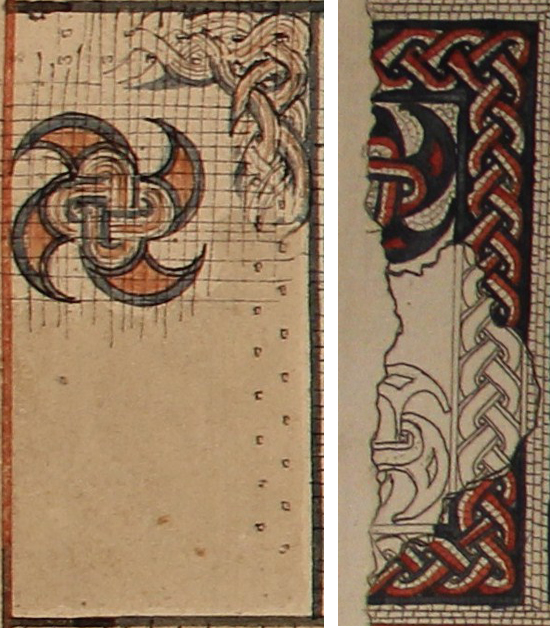

In July 2014, The Collection museum in Lincoln acquired an original hand-drawn illustration of this pavement from a local antique shop (fig 3). The provenance of this new illustration is sadly unknown, and inferences as to its origins have to be made purely from the illustration itself.

Fig 2: William Fowler's illustration, first published in 1800. The Collection, LCNCC : PD35

Fig 3: Newly acquired illustration. The Collection, LCNCC : 2014.167

Aside from the fact that they depict the same tessellated pavement (though Fowler's published illustration shows the western edge uppermost and the new illustration the eastern edge), the two illustrations are almost identical. One major difference, however, is that Fowler's engraving is clearly attributed to him as illustrator and producer ('Wm Fowler del et fecit') and as being published by him on May 1st 1800. Cayley Illingworth notes in his book that Fowler's drawing was made 'several years since … without any view to this work' [7], referencing this 1800 publishing date. The new illustration in contrast is unsigned and undated.

The titles of both illustrations follow a consistent format, with only two minor differences. The printed title on Fowler's engraving reads 'Roman Tessellated Pavement discovered by the Revd. Cayley Illingworth, upon the estate of Richard Stonhewer Esqr. at Scamton [sic] near Lincoln in the year 1795.' The handwritten title on the new illustration differs only in that 'tessellated' is spelled with only one 'l' and Scampton appears with a 'p'. The new illustration contains an additional note in the same hand which reads 'at Mr Stonhewer's death the estate went to Sir George Cayley.' A terminus post quem for this additional note is provided by the 1810 reprint of Cayley Illingworth's Scampton book, which records that Richard Stonhewer died at 80 years old on 30th January 1809 [8].

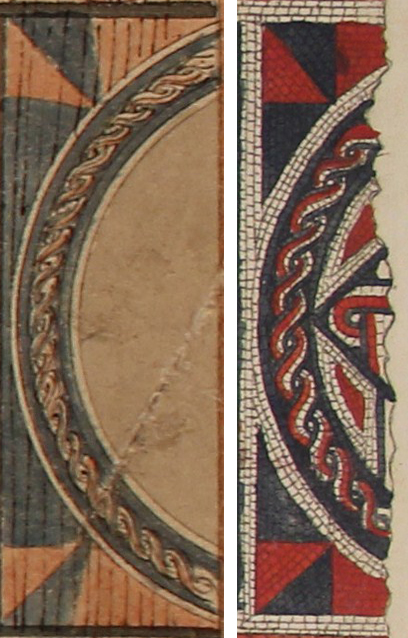

The identity of the creator of the new illustration is therefore the key question. Is it an early sketch by William Fowler, originally created prior to the version he published in 1800 and subsequently used by Cayley Illingworth? The details of the illustrations suggest that this is not the case. Fig 4 shows a comparison of the same panel from both illustrations, Fowler's on the left and the new illustration on the right. That the new illustration is a rougher sketch is clear to see, as is the fact that the individual tesserae have not been individually demarked, instead represented rather crudely with a grid. Fowler's drawing clearly shows individual tesserae, though of course the veracity of these is now unprovable and the accuracy of the rendering of individual tesserae to be doubted.

Fig 4: Comparison of one panel from both illustrations

The broken northern (fig 5) and southern (fig 6) ends of the pavement are worthy of comparison, as the only areas where the two illustrations differ in their depictions of the pattern and its level of preservation.

Fig 5: Comparison of northern termination of pavement

Fig 6: Comparison of southern termination of pavement

In both instances, Fowler's published illustration (on the right) includes additional details omitted from the new illustration. Of course, without reference to the original pavement, we cannot say which is the more accurate record, but we can postulate that the illustrations were carried out by a different hand and the differences not merely those between first draft and published copy.

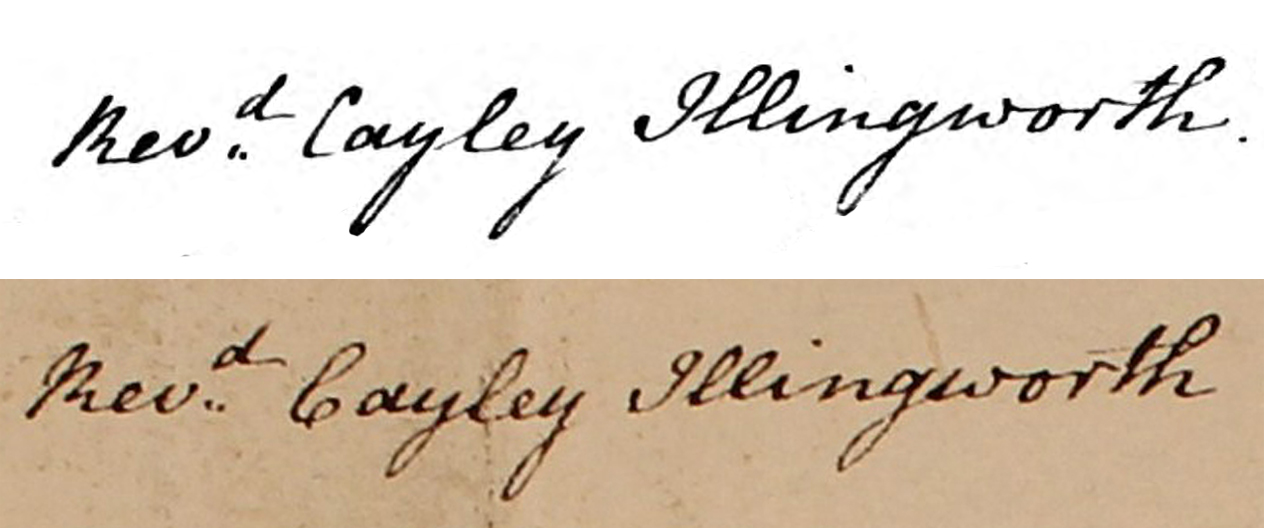

Analysis of the handwritten title on the new illustration provides two hints that its creator was none other than the Reverend Cayley Illingworth himself. An 1808 copy of his book, now in Oxford University's Bodleian Library, is one originally given by Cayley Illingworth to Edward Weston of Somerby, and inscribed with a handwritten note. Comparison of Cayley Illingworth's name on both this inscription and the new illustration (fig 7) clearly demonstrates that the handwriting is the same. Further evidence is provided through the additional note on the illustration referencing the change of land ownership following Richard Stonhewer's death. That the land passed into the ownership of Sir George Cayley would surely be of no interest to Fowler, but of particular relevance to Cayley Illingworth. It seems likely, therefore, that the illustration was produced at some point between 1795 and 1809. Given that Fowler published his illustration in 1800, it is possible that Cayley Illingworth's illustration predates that, and was made in the years immediately following the unearthing of the pavement.

Fig 7: Comparison of handwriting on 1808 book (top) and illustration (bottom)

Why, then, did Cayley Illingworth not publish his own illustration in his book? He included illustrations by various artists, including a frontispiece by his own daughter, Sophia. Perhaps modesty played a part, or perhaps the fame that Fowler had attained meant that he had no choice but to use his illustration. Whatever his reasons, his illustration has thankfully survived and now forms part of the formal record of the discovery and recording of this important archaeological site.

Antony Lee

Lincoln

August 2014

_________________________________________________

[1] Cayley Illingworth, Rev; 'A Topographical Account of the Parish of Scampton in the County of Lincoln and of the Roman Antiquities lately discovered there; together with anecdotes of the Family of Bolles; 1810; pg 3

[2] ibid, pg 9

[3] ibid, pg 13

[4] ibid, pg 12

[5] ibid, pg 6

[6] ibid, pg 10

[7] ibid, pg 9

[8] ibid, pg 52

Comments

A really illuminating article

steve kentDoes anyone know if this paving is buried or was it destroyed by subsequent ploughing? Such a shame that it couldn’t be turned into a museum like the Bognor site in West Sussex

Jennifer Taylor