Antiquarian recording of Lincoln’s Newport Arch

RSS FeedHumans have always had an interest in their own history, from the Greeks and Romans creating myths to explain their origins to prehistoric handaxes found on Medieval settlements, no doubt found in fields and retained as objects of antique curiosity and mystery. It was in the 18th Century, however, that Britain saw a flourishing of historical interest and the development of antiquarianism - a realisation that the physical and tangible remains of the past were all around in the landscape, that they could be studied to reveal their secrets, and that they might not last forever and should be recorded in as scientific a manner as possible.

In Lincolnshire, early pioneers of this new fascination with ancient history included men such as William Stukeley (1687-1765), a Holbeach born lawyer who would become most famous for his theories on Stonehenge, Thomas Sympson (1702-1750) a librarian at Lincoln Cathedral, and Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, prolific illustrators of historic monuments and townscapes across Britain. A great many other less famous names also began to record the historic remains around them, and their records are no less valuable.

In Lincoln, one monument that attracted much attention was the Roman Newport Arch. Its great age had long been recognised (though the exact date of its construction not always accurately estimated) but it was clear that the remains had been altered over time, and much that had been standing in the 15th and 16th Centuries was becoming lost. In a world without heritage protection legislation, the survival of monuments was a matter of chance, and it sometimes seems a miracle that some have survived at all in the face of individual greed, ignorance and the march of progress.

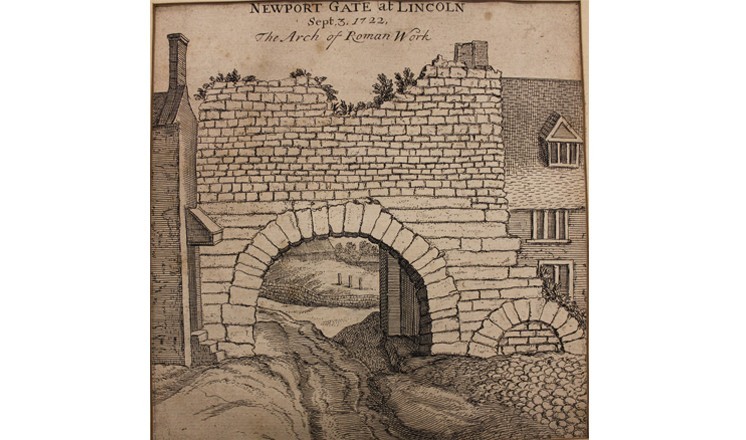

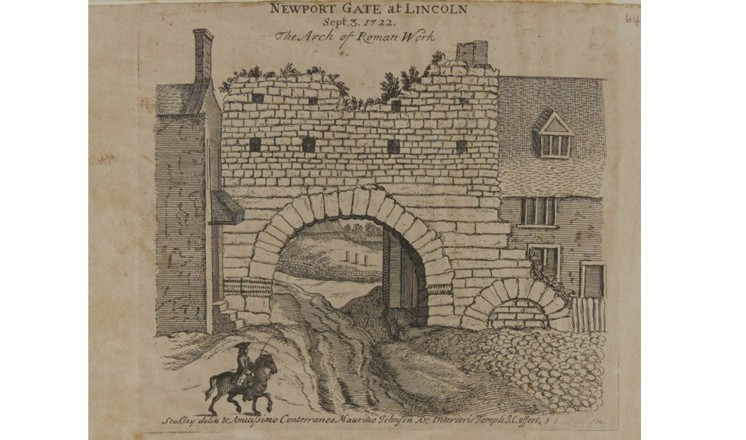

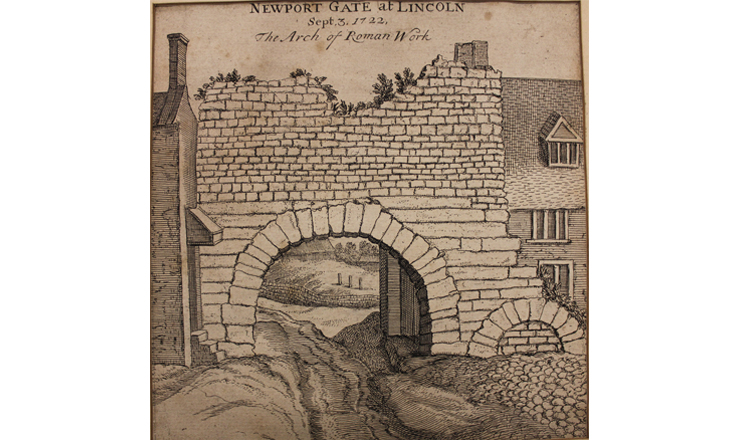

The earliest illustrations of the arch in the museum's collections are those by William Stukeley in 1722. His stiff style records the arch very much tightly pressed on both sides by buildings, and with the surviving pedestrian arch still blocked. The high road level is also of note, the main arch looking as if a wheeled vehicle would struggle to safely pass underneath, Interestingly, we have two versions of this drawing, one purely of the arch and another with a figure on horseback in the forground. Perhaps this latter version was produced for a specific publication, though if added for scale, the figure is rather small. Interestingly, this second illustation also includes two rows of putlog holes not featured on the first, and not visible on the arch today.

Our next depiction is dated 1756 and is by the Lincoln born artist Nathan Drake (c.1728-1778). This oil painting captures the remains in a more romantic fashion than Stukeley, though the basic depiction of the arch remains consistent. Drake's focus is as much on the arch being the setting for everyday life, with an ox cart passing through, women at work and the gentry involved in conversation. Note that a faint single line of putlog holes can be seen above the arch.

A slightly less artistically accomplished engraving was produced by S Hooper (dates unknown) in 1784. Again, the closeness of the buildings to the arch can be seen, and the focus is as much on putting the arch into its contemporary setting than on accurately recording the remains, though the details of the arch remain consistent with the previous depictions. This illustration portrays the arch in such a similar way to Stukeley's 1722 drawings that it is possible to suggest that Hooper took Stukeley's work as a basis for his own illustration, though the putlog holes are not depicted.

In the late 18th Century (the date sadly unknown), Bartholemew Howlett (1767-1827) produced the eariest image we have of the arch from the north. Stukeley, Drake and Hooper had illustrated the arch from the south, looking from inside the Roman city to the outside, the view of the arch which is still most famous. By capuring the other side of the arch, Howlett provides us with a view much different to that seen today.

Although the various vaulting arches are impossible to date from the drawing, it is clear that much more of the rear of the arch suvived than today, making this an important record of the arch's decay in the intervening years.

Are you aware of any other 18th Century illustrations or paintings of Newport Arch that we haven't included here? Let us know in the comments!

Comments

James Valentine photographed the arch around 1856 and it was included in the collections of Thomas Annan. https://brewminate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Annan23.jpg

John Smith